Complexity Mapping

Overview

Destructive conflicts demand attention to the here and now; to the violence, hostilities, suffering and grievances evident in the immediate context. While important, this emphasis often draws attention away from the history, trajectory, and broader context in which the conflict is evolving. Today, many peace-practitioners employ the use of complexity and feedback-loop mapping to re-contextualize their own and the stakeholders’ understanding of the conflict (see Burns, 2007; Coleman, 2011; Körppen, Ropers & Giessmann, 2011; Ricigliano, 2012).

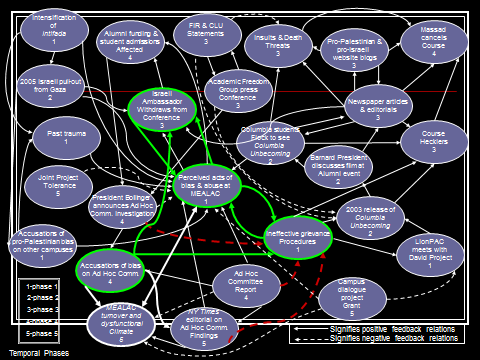

The dynamical system of the conflict – in the form of a dynamic network – can be represented through a series of feedback loop analyses (see Figure 1). Loop analysis, developed by Maruyama (1963, 1982), is useful for mapping reinforcing and inhibiting feedback processes that escalate, de-escalate and stabilize destructive conflicts. Reinforcing feedback occurs when one element (such as a hostile act) stimulates another element (such as negative out-group beliefs) along its current trajectory. Inhibiting feedback occurs when one element inhibits or reverses the direction of another element (such as when guilty or compassionate feelings damper hostilities). Strong attractors are created when reinforcing feedback loops are formed between previously unrelated elements, while inhibiting feedback dissipates in the system.

Feedback mapping not only captures the multiple sources and complex temporal dynamics of conflict systems but can also help identify central nodes and patterns that are unrecognisable by other means. The process typically begins by identifying the key elements in the conflict that emerge during different phases of escalation and specifying the nature of the linkages among these elements. This analysis can be characterized as evolving through various developmental stages (such as phases 1-9 in Figure 1). Maps can be generated at the individual level (identifying the emotional and cognitive links that parties hold in their attitudes, feelings and beliefs – associations related to the problem and to their sense of the other), at the interpersonal level (allies, enemies, power structures and so on.) and at the systemic level (e.g. mapping the feedback loops that allowed a particular series of events to escalate, such as seen in Figure 1). This can be useful for remaining mindful of the systemic context of the conflict and for restoring a sense of complexity into the parties’ understanding of events.