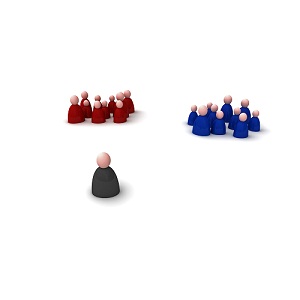

While a large body of previous research has focused on the way conflict escalates between two parties, we know much less about how it spreads to involve others, a phenomenon known as third party conflict contagion. In a study recently published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, Lee and colleagues (2014)1 investigate third party conflict contagion’s role in the escalation and distortion of conflict narratives. In their study, participants formed 4-person “chains” in which each member read and re-told a given conflict narrative. Participants were never informed of their position in the chain, and were instructed to type out their reproduced narratives on a computer for the next member of the chain. Analyses focused on participants’ reactions to the conflict as well as linguistic- and content-coding of the re-told narratives across each chain.

Findings revealed that successive generations became increasingly biased in their evaluations of the parties involved in conflict, in their attributions of responsibility or exoneration, and even in their motivations for revenge. Narratives became increasingly biased when it came to language depicting misconduct or moral integrity, and were exaggerated in their tone of blame or sympathy. These communication biases increased with each iteration of the chain, resulting in meaningful escalations and distortions from the original conflict. Importantly, these results were only true for partisan third parties (participants told to imagine themselves as friends to one of the groups), but not for neutral third parties. Thus, by reading conflicts in which friends were involved (as opposed to conflicts in which neither group included friends), chains were more inclined to distort information (for example, by blaming the ‘outgroup’ and exonerating the ‘ingroup’). The accumulation of distortions led to biases that emerged and escalated over time, going well beyond initial ingroup favoritism.

Such research has wide-ranging implications, from everyday gossip to formal conflict mediation techniques. Across this spectrum, findings strongly suggest that third parties should hesitate to accept conflict descriptions at face value. Beyond questioning their authenticity, third parties should also use discretion in their own reproductions of conflict narratives in order to avoid further biases for subsequent audiences. Though such research certainly tells a cautionary tale, it also provides valuable insights into the role of third parties in conflict escalation, inciting research to go beyond more traditional two-party approaches.

1 Lee, T.L., Gelfant, M.J., & Kashima, Y (2014). The serial reproduction of conflict: Third parties escalate conflict through communication biases. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 54: 68-72.