Research Overview

Conflict Intelligence

Today, the pace, complexity and volatility of our personal and professional worlds are increasing exponentially. These conditions create pressures conducive to heated conflict, which can distract and distance us from one another and derail relationships and productivity. Or, they can energize and mobilize innovation, creativity, connectedness and group effectiveness. The issue is whether or not conflict is managed intelligently.

Conflict Intelligence (CIQ) is simply knowing how and when to use different strategies to respond to distinct types of conflict effectively.

At the MD-ICCCR, our research focuses on developing new insights into the CIQ competencies required to navigate differences more effectively in our new era of increasing complexity. Our research seeks to answer the question: What are the types of knowledge, skills, and competencies needed to navigate different kinds of conflicts—in fundamentally different kinds of situations—effectively and constructively?

We combine insights from psychology, peace and conflict studies and complexity science to offer revolutionary new ways to:

- Negotiate conflicts across power differences

- Mediate conflicts adaptively when they involve highly intense, constrained, competitive or hidden conflicts that are hard to talk about

- Address cross-cultural conflicts and intergroup disputes that involve gender, religion or

political differences - Leverage the energy from conflicts in organizations to help to promote the transformation

of institutionalized forms of bias and discrimination - Work with more difficult, polarizing, complex conflicts that resist resolution, such as those plaguing much of our society today

Click on the (+) buttons below to learn more about each of these areas of research:

What are the types of knowledge, skills, and competencies needed to navigate different kinds of conflicts—in fundamentally different kinds of situations—effectively and constructively?

Overview

Through our work at the lab, we’ve identified two meta-competencies—Conflict Intelligence and Systemic Wisdom—for adaptively managing different kinds of conflicts across contexts, and for transforming entrenched patterns of conflict. These represent two distinct but complementary competencies or modes of conflict engagement, which are associated with distinct types of conflict. The Conflict Intelligence and Systemic Wisdom framework differentiates conflicts according to their levels of complexity, destructiveness, and endurance over time, and suggests that variation along these 3 dimensions calls for distinct strategies and orientations:

Conflict Intelligence is most effective for addressing conflicts of low-to-moderate importance and intensity, where extreme forms of enmity, injustice and violence are rare. Our temporal scope in these disputes is usually more immediate or short-term, and our aim is to directly engage the problem, relationship, or other disputants. In contrast, Systemic Wisdom refers to the capacity to understand the inherent propensities of the complex, dynamic context in which a conflict is embedded—and the capacity to work with the dynamics of the system to support the emergence of more constructive patterns.

Systemic Wisdom is required in conflict situations that are more complex, destructive, and enduring. In these contexts, often times the more straightforward strategies of conflict resolution fail to have the desired effect, and sometimes they bring about unintended consequences that can perpetuate existing problems.

Current Projects

- Conflict Anxiety Response Scale (CARS) development study

- Implicit Conflict Theory assessments

- Development of full CIQ and SW Assessment package

Selected Empirical Studies and Publications:

- Coleman, P. T. (2018). Conflict intelligence and systemic wisdom: Meta-competencies for engaging conflict in a complex, dynamic world. Negotiation Journal, 34(1), 7-35.

- Recipient of the International Association of Conflict Management 2017 Best Conference Theoretical Paper Award.

- Coleman, P. T. & Lim, Y. Y. J. (2001). A systematic approach to evaluating the effects of collaborative negotiation training on individuals and groups. Negotiation Journal, 17(4), 329-358.

How do differences in power, goals and dependence affect conflict dynamics and how can they be navigated adaptively and constructively?

Overview:

Based on decades of research, we know that managing conflict up and down the chain of command in organizations can be particularly treacherous, as power differences complicate conflict situations and constrain options for responding. Our work on what we call Adaptive Negotiation explains why these pitfalls are so common and how to take advantage of the energy and potential for change that such situations create.

Our book, Making Conflict Work: Harnessing the Power of Disagreement, offers seven strategies and dozens of tactics for increasing your Conflict Intelligence and finding greater success and satisfaction through conflict.

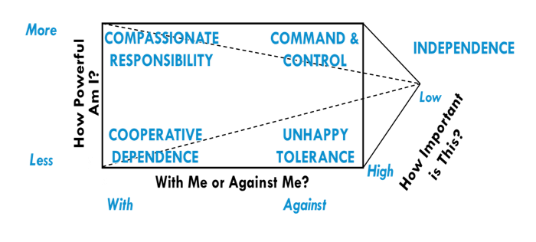

Using a model of power and conflict derived from our empirical research, we help people identify the right questions for diagnosing the kind of situation they’re in:

- How important is the conflict?

- Are the other disputants with me, or against me?

- Am I more or less powerful than them?

Based on an understanding of these three dimensions, people can begin to determine what kind of situation they’re in, to examine their typical or chronic tendencies in conflict, and to begin to work more intentionally to match their strategies to the demands of the situation they’re in.

Our research tells us that adaptively matching your strategy in conflict to the specific demands of the situation leads to more satisfaction with conflict at work, satisfaction with work in general, greater overall emotional well-being, and improved relationships with co-workers. Among leaders, adaptivity leads to more candor and more honest feedback from staff, as well as more innovative thinking, insights, and creativity from staff.

Current Projects

- Conflict Intelligence Assessment (CIA)

- Making Conflict Work executive education modules and workshops

Select Empirical Studies and Publications

- Coleman, P. T. and Ferguson, R. (2014). Making Conflict Work: Harnessing the Power of Disagreement. New York: Houghton-Mifflin-Harcourt.

- Coleman, P. T., Kugler, K., Musallam, N., Mitchinson, A., and Chung, C. (2010).The view from above and below: The effects of power asymmetries and interdependence on conflict dynamics and outcomes. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 3, 283-311.

- Coleman, P. T., Kugler, K. G., Bui-Wrzosinska, L., Nowak, A., and Vallacher. R. (2012). Getting down to basics: A situated model of conflict in social relations. Negotiation Journal, 28(1), 7-43.

- Coleman, P. T., Kugler, K. G., Mitchinson, A., and Foster, C. (2013). Navigating Power and Conflict at Work: The Effects of Power Asymmetries on conflict in organizations. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(10), 1963-1983.

- Coleman, P. T., and Kugler, K. G. (2014). Tracking managerial conflict adaptivity: Introducing a dynamic measure of adaptive conflict management in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(7), 945-968.

- P. T., Vallacher, R., & Nowak, A. (2012). Tackling the great debate: Nature-nurture, consistency, and the basic dimensions of social relations. In P. T. Coleman (Ed.), Conflict, Cooperation and Justice: The Intellectual Legacy of Morton Deutsch. Springer.

- Coleman, P.T., (2014). Power and Conflict. In P. T. Coleman, M. Deutsch, and E. Marcus (Eds.) The Handbook of Conflict Resolution: Theory and Practice, 3rd San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

- Coleman, P. T. (2004). Implicit Theories of Organizational Power and Priming Effects on Managerial Power Sharing Decisions: An Experimental Study. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(2), 297-321.

- Deutsch, M. (1982). Interdependence and psychological orientation. In Cooperation and helping behavior: Theories and research, edited by V. Derlegaand and J. L. Grzelak. Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

What are the most basic challenges to mediation, and how do mediators effectively adapt and respond to them as they ebb and flow in conflict situations?

Overview

Although mediation has increased considerably in popularity and usage, it lacks a coherent framework and evidence base to illuminate the conditions under which different types of mediation strategies are most effective. This has resulted in a wide array of strategies and tactics being offered to mediators, with little sense of which may work best under different conditions.

This area of research aims to further develop a contingency model of adaptive mediation. Through a series of surveys, interviews, and focus groups, we’ve developed a model that reflects the most important situational characteristics of mediation that affect mediators’ decisions and behaviors.

Our Situated Model of Adaptive Mediation argues for the utility of an adaptive or situationally contingent approach to mediation, where mediators learn to employ different strategies in response to fundamentally different challenges they face in mediations.

Through this research, we’ve identified four challenges that are most consequential to mediations:

- First is conflict intensity. How intensive, emotional, destructive, and complex is the conflict?

- Second is the quality of relations between the parties—in other words, are they more cooperative or competitive?

- Third is the level of constraint—is the context more flexible or tight?

- And finally, fourth we look at the degree of overt versus covert processes—how obvious or hidden are the issues and processes?

Based on these four challenges, we identified five main approaches or strategies for most adaptively mediating across different constraints:

|

SITUATION TYPE |

MEDIATION STRATEGY |

|

Low intensity, cooperative, low constraint, and overt issues |

Standard Mediation—focus on open dialogue designed to surface, explore, and resolve issues |

|

High Intensity |

The “Medic”—focus on managing or lessening intensity by being active, present, and directive in reinforcing guidelines |

|

Highly Competitive |

The “Referee”—bargain fairly and settle efficiently by providing guidance and direction and by focusing on creating a sense of safety |

|

Highly Constrained—Time and Resources |

The “Fixer”—openly address constraints, clearly outline the structure and guidelines, and offer directive guidance to efficiently work through the mediation process |

|

Highly Covert Issues |

The “Therapist”—probe deeply and carefully for underlying issues, coach the participants, focus on creating a safe space for deeper exploration |

In our research, adaptive mediation refers to the capacity to read important challenges to mediation situations and to respond to them with strategies and tactics that are more “fitting” and thus more effective in those situations.

Current Projects

- Dynamic Network Theory (DNT) with Jim Westaby

- Mediation Adaptivity Assessment Tool (MAAT)

Select Empirical Studies and Publications

- Coleman, P. T., Kugler, K. G., and Chatman, L. (2017). Adaptive mediation: An evidence-based contingency approach to mediating conflict. International Journal of Conflict Management, 28(3), 383-406.

- Recipient of the International Biennial on Negotiation Conference Best Paper Prize, November 17th, 2016.

- Coleman, P. T., Kugler, K, & Mazzaro, K. (2016). Getting beyond win-lose and win-win: A situated model of adaptive mediation. In K. Bollen, M. Euwema, & M. Lordea (Eds.), Advancing workplace mediation: Integrating theory and practice. Springer Verlag.

- Coleman, P. T., Kugler, K., Gozzi, C., Mazzaro, K., El Zokm, N & Kressel, K. (2015). Putting the peaces together: Introducing a situated model of mediation. International Journal of Conflict Management, 26(2), 145-171.

- Kugler, K. G., and P. T. Coleman. (Working paper). The effects of adaptive mediation on mediator satisfaction, empowerment and efficacy.

- Westaby, J. D. (2012). Dynamic network theory: How social networks influence goal pursuit. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

What are the most basic conditions that determine whether more locally informed, elicitive versus more empirically informed, prescriptive models and methods are best employed to address peace and conflict when working across cultures?

Overview

Research on cross-cultural conflict management has offered the distinction between more prescriptive versus more elicitive approaches to intercultural conflict resolution training and intervention (Lederach 1995; Weller, Martin, and Lederach 2001).

More prescriptive approaches privilege the information and strategies introduced by a conflict resolution expert (negotiation, mediation, dialogue, training, etc.), while more elicitive approaches favor local contextual knowledge and expertise for addressing conflict and peace.

Although proponents offer more elicitive approaches as a check on the bias and cultural imperialism evident in many Western approaches to cross-cultural conflict, they concede that it is often not feasible or practical to employ. Currently, we are investigating the basic conditions conducive to using more elicitive versus more prescriptive approaches.

Based on a literature review and initial survey, we’ve begun to explore characteristics of actors—such as cultural bias awareness, cultural familiarity, cross-cultural access and partnerships, and resource availability—characteristics of stakeholders—such as objectives, community commitment and agency, and levels of egalitarianism—and the cultural tightness or looseness of the context to better understand the conditions that make more prescriptive or elicitive intervention approaches more appropriate and constructive.

Current Projects

- Cross Cultural Adaptivity (CCA)

- Individualism-Collectivism Optimality (I-C)

Select Empirical Studies and Publications

- Coleman, P. T., Mah, E., and Kim, R. (Working paper). Cross-cultural adaptivity in conflict: Mapping the conditions for prescriptive versus elicitive intervention and training.

- Kim, R. and Coleman, P. T. (2015) The Combined Effect of Individualism – Collectivism on Conflict Styles and Satisfaction: An Analysis at the Individual Level. Peace and Conflict Studies, 22,

How can we leverage tension from multicultural conflict to help break down destructive, change-resistant patterns of intergroup bias and discrimination and help promote more constructive patterns of fair and just workplace reform?

Overview

Enduring forms of bias and discrimination are well documented and pervasive in many organizations fueling costly patterns of destructive cross-cultural and multicultural conflict. Changes in these dynamics are often slow and beset with setbacks.

In this area of research, we propose a dynamical systems model of multicultural organizational change, which outlines how leveraging tension from such conflict can help break down destructive multicultural attractors, or change-resistant patterns of intergroup bias and discrimination, and help promote more constructive attractors through increased institutional accountability for enacting fair and just workplace reforms.

By recognizing the complex, self-reinforcing, and dynamic nature of patterns of bias and discrimination, and by working with the resulting tensions optimally and strategically, we propose that these tensions can provide energy and will for reforms that transform chronic patterns of multicultural relations from destructive to constructive.

Current Projects

- Constructive Multicultural Organizational Development (CMOD)

- Optimal Tension/Leveraging Tension for Constructive Multicultural Conflict (OT)

Select Empirical Studies and Publications

- Coleman, P. T., Coon, D., Kim, R., Chung, C., Regan, B., Anderson. R., & Bass, R. (2017). Promoting constructive multicultural attractors: Fostering unity and fairness from diversity and conflict. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 53(2), 180-211.

- Castro, M. K., & Coleman, P. T. (2014). Multiculturalism and Conflict. In Peter T. Coleman, Morton Deutsch and Eric C. Marcus (Eds.) The Handbook of Conflict Resolution: Theory and Practice (3rd Edition). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Chen-Carrel, A., Bass, R., Coon, D., Hirudayakanth, K., Ramos, D., and Coleman, P. (Working paper). Leveraging tension for constructive multicultural conflict within workplaces.

Why do some types of conflicts come to seem intractable and impossible to resolve, and what can we do to address them constructively and sustainably?

Overview

Research on difficult conflicts tells us that roughly five percent of them become intractable: they enrage us, frustrate us, trap us, drain us of energy and other critical resources, and seem to resist all good faith attempts to resolve them. These conflicts often escalate into long-term malignant processes with high social and economic costs, eventually appearing boundless and hopelessly unsolvable.

Our scholarship on intractable conflict has focused on improving our understanding of the unique dynamics involved in intractable conflicts—both generally as whole systems, as well as specifically through the investigation of key components of these problems.

Our research has consistently found that fostering and supporting more complex patterns of thinking, feeling, identifying, acting, and social organizing in systems can prevent or mitigate destructive conflict, resulting in more robust patterns of constructive conflict dynamics. In this area of research, we are developing innovative methodologies to identify and explore these complex patterns with the goal of developing tools for applying emerging insights.

To access a series of brief video introductions to conflict intractability click here.

Featured Project

In our Difficult Conversations Lab, we have begun to investigate the underlying emotional, cognitive and behavioral dynamics of disputants engaged in particularly difficult and divisive conflicts over time.

We have designed a series of studies to test our dynamical model (i.e. a model that takes into account how factors in conflict dynamically change over time and in relation to other contextual factors) by addressing two questions:

- What are the underlying dynamics of moral conflicts that lead to more satisfying positive outcomes versus more dissatisfying negative outcomes, and,

- What basic parameters determine qualitative differences in these dynamics?

In order to study these dynamics under as authentic conditions as possible, participants in our studies engage in discussions over important moral issues—including the death penalty, abortion, affirmative action, and euthanasia—on which they disagree while their emotional, cognitive and behavioral dynamics are measured and analyzed.

Current Projects

- Difficult Conversations Lab (DCL)—Featured in articles:

- Make America talk again: the lab teaching sworn enemies to have decent conversations, in The Guardian

- How to Handle Difficult Conversations at Thanksgiving, in The New York Times

- Complicating the Narratives: What if journalists covered controversial issues differently — based on how humans actually behave when they are polarized and suspicious?, in Solutions Journalism

- Divided America, difficult conversations: If you're ready to have them, here's how, in The Chicago Tribune

- It’s Impossible to Talk to You, Anyway, in Die Zeit

- Liberal-Conservative Optimality Model

- Liberal-Conservative Adaptivity Model

- Resonance

- Organizational Conflict and Complexity

- Getting in Sync:

- Leadership Complexity Competencies

Select Empirical Studies and Publications

- Fisher, J. & Coleman, P. T. (2018). The fractal nature of intractable conflict: Implications for sustainable transformation. In L. Kriesberg, L. & C. Gerard (Eds.) Transforming Intractable Conflict. Rowman and Littlefield International.

- Coleman, P. T., Redding, N., & Fisher, J. (2017). Understanding Intractable Conflict. In A. Schneider & C. Honeyman (Eds.), The Negotiator’s Desk Reference. Chicago: American Bar Association Books.

- Coleman, P. T., Redding, N., & Fisher, J. (2017). Influencing Intractable Conflict. In A. Schneider & C. Honeyman (Eds.), The Negotiator’s Desk Reference. Chicago: American Bar Association Books.

- Coleman, P. T., & Ricigliano, R. (2017). Getting in Sync: What to do when problem solving fails to fix the problem. In A. Schneider & C. Honeyman (Eds.), The Negotiator’s Desk Reference. Chicago: American Bar Association Books.

- Coleman, P. T. (May 3, 2011). The Five Percent: Finding Solutions to (Seemingly) Impossible Conflicts. New York: Public Affairs, Perseus Books.

- Vallacher, R., Coleman, P. T., Nowak, A., Bui-Wrzosinska, L., Kugler, K., Bartoli, A., & Liebovitch, L. (2013). Attracted to Conflict: Dynamic Foundations of Malignant Social Relations.

- Coleman, P. T. (forthcoming). UnHero: A Counterintuitive Guide to Effective Leadership.

All of our research draws concepts from Dynamical Systems Theory (DST), a branch of applied mathematics and complexity science, to provide conceptual models of conflict and peace that contextualize our views of the phenomena across time and in more complex contexts.

DST argues for the need to move beyond the study of conflict in terms of the effects of isolated, distinct elements (i.e. issues, individuals, motives, conditions and agreements), or even interactions between elements, toward a focus on the underlying feedback dynamics at play in conflict systems that lead to more or less constructive and destructive patterns of social relations over time.

What is a Dynamical System

A dynamical system is simply a set of interconnected elements (such as beliefs, feelings, actions and norms) that change and evolve together in time, eventually settling into some form of higher-order pattern.

Together, the connected elements constitute a system that evolves as each element adjusts to the joint influences of others.

Rather than emphasizing causal links between elements (in which A causes B), the elements are seen as affecting one another through two types of feedback loops – reinforcing loops (in which A and B support and reinforce one another) and inhibiting loops (in which A and B obstruct or constrain each other). This shift from links to loops broadens our focus from shorter-term effects to longer-term dynamics.

In other words, DST helps us understand the non-linear networks of influence within complex systems.

The Key Ideas

- Emphasizes the longer-term temporal patterns of conflict dynamics in social systems rather than only episodic events or short-term interactions and outcomes;

- Recognizes that these patterns are often affected by a complex constellation of factors (attitudes, beliefs, norms, policies, structures and so on) that interact over time;

- Suggests that some parameters associated with conflict dynamics are likely to have a stronger impact on qualitative changes in the patterns of the system than others, an idea known as dynamical minimalism.

If you’re interested in more in-depth information about DST and its applications, please visit our AC4 partner page at: http://ac4.ei.columbia.edu/research-themes/dst/

Select Empirical Studies and Publications

- Vallacher, R. R. & Nowak, A. (2007). Dynamical Social Psychology: Finding Order in the Flow of Human Experience. In A. W. Kruglanski & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles, 2nd Edition, (pp. 734-758). New York: Guilford Publications.

- Vallacher, R., Coleman, P. T., Nowak, A., Bui-Wrzosinska, L. (2010). Rethinking intractable conflict: The perspective of dynamical systems. American Psychologist, 65 (4), 262-278.

- Svyantek, D. J., & Brown, L. L. (2000). A complex-systems approach to organizations. Current Directions in Psychological Science,9, p. 69-74.

- Gottman, J., Gottman, J., Greendorfer, A. & Wahbe, M. (2014). An Empirically-Based Approach To Couples’ Conflict. In Peter T. Coleman, Morton Deutsch and Eric C. Marcus (Eds.) The Handbook of Conflict Resolution: Theory and Practice (3rd Edition). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Vallacher, R., Coleman, P. T., Nowak, A., Bui-Wrzosinska, L., Kugler, K., Bartoli, A., &

- Liebovitch, L. (2013). Attracted to Conflict: Dynamic Foundations of Malignant Social Relations. Springer.